Igor Vidor

from Brazil, born in 1985, photographer, visual artist, and, since July 2019, MRI scholarship holder at the host organisation Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin.

Nine friends of Igor Vidor have been killed by the Brazilian police. Among them, his childhood friend Rodrigo. That was in 2016; Vidor was artist-in-residence at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in South Korea when the news reached him. It was a shock, and perhaps the greatest turning point in his life, artistically and personally.

‘I just thought: why? Why like this? Twelve gunshot wounds and broken ribs. Wouldn’t one shot have been enough? Or arresting him?’ asks Vidor.

The connection between poverty, money flows and violence

Rodrigo was killed by police violence. He was a drug dealer and had already climbed high in the hierarchy – but did that make him less of a victim? Vidor wondered. Had his friend therefore forfeited all rights? The two of them had played football together as children, grew up together, and then took different paths. And so Vidor began to question the connections – between poverty, skin colour and advancement, between money flows and violence – and to show them in his art.

‘I began doing research’ says Vidor. ‘Why do some of us live in safety and others not; what does safety mean? And then I understood: we’re talking about security, but I call it the “Business of Protection”. The business of protection needs to produce insecurity in order to sell protection. That is like an equation. In the end, it’s all about money and profit.’

Staging aggression and power

Vidor grew up in a poor neighbourhood in São Paulo. ‘It was a very violent environment. Violence was prevalent in the streets, and was also practiced by the police’, he says. He went to the local art college on a scholarship, moved, and began studying philosophy and sociology.

In his first years as an artist, Vidor was mainly concerned with the social conditions and divisions in Brazil. In 2016, he broadened this perspective and has since directed it to the subject of state violence, increasingly also to the media presentation of crime, power and aggression, and to the global interrelationships between arms production, marketing strategies and their

Carne e Agonia

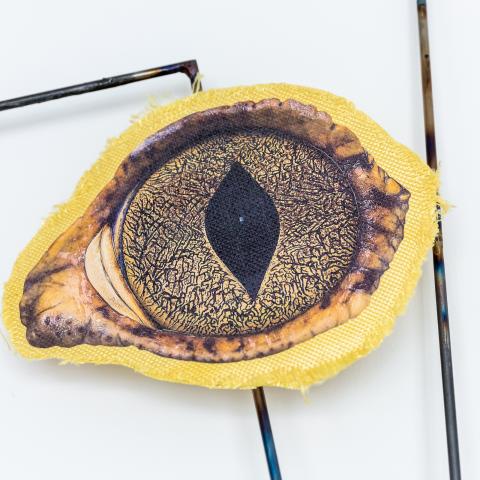

Vidor often makes use of symbolic objects – for example umbrellas, whose carriers were shot because the police confused them for weapons. He works with aramid fabrics, from which bulletproof vests are made, and glues to them pictures of the aggressive wild beasts that police units have chosen to be their heraldic animals (Beasts, 2020). ‘Every day in Brazil is about violence – symbolic and real violence’, explains Vidor. That is why it is important for him as an artist to find a mode of expression that addresses but doesn’t reproduce violence.

In an exhibition in São Paulo in 2018, Vidor showed his video Carne e Agonia: pictures of weapon tests are subtitled with interview statements by a police officer and a drug dealer – without the viewer knowing who is giving the respective answers. After the exhibition, Vidor received such alarming death-threats that he had to hire bodyguards, move several times, and ultimately leave the country.

Change of perspective

Thanks to the Martin Roth-Initiative, Vidor has been working since July 2019 at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. There, he has further developed his subject, and exhibited his work at various art venues, including the Berlinische Galerie. And: being far from home has sharpened his perspective as some of the weapons that are used in Brazil are produced in Germany. ‘I’m very grateful that I can work here’, emphasises Igor Vidor. ‘But I hope that in the exhibitions here I can make clear that democracy is also a global issue: if we’re fighting for the rainforest in Brazil, shouldn’t we also fight for the lives of the people there?’

The Künstlerhaus Bethanien is an international cultural centre in Berlin. As a studio house and workplace for professional artists, and a multi-layered project workshop and event location, it has set itself the goal of promoting contemporary visual arts. Its chief focus is an international studio programme, in which artists from all over the world develop and present projects every year.

(translated from German into English)

Text: Marion Meyer-Radtke; editing: MRI

Photos/video: Rolf Schulten

Audio slideshow design: Johanna Barnbeck